How the monetary system works, part 1 – deposits, reserves and bank notes

What is happening in the economy and the markets?[1] How can financial markets – or certain important parts of them, including most notably US markets for large-market-cap equities and corporate credit – be booming when businesses are shut, millions of people are out of work and a huge wave of personal and corporate insolvencies seems inevitable?

Most answers point to the actions of the Federal Reserve and other central banks, who have been carrying out something called quantitative easing, or ‘QE’.

Through QE central banks increase their balance sheets by creating the means to buy financial assets. Many describe this as printing money and worry that doing so on this massive scale must result in inflation. After all, didn’t Milton Friedman once say that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”? Haven’t we learned from Zimbabwe and Weimar Germany?

Others say that isn’t right: when central banks buy assets, they buy them from banks and pay for those assets with something called ‘bank reserves.’ They correctly point out that bank reserves are not money in the usual sense, because they just pile up in the banks’ accounts at the central bank and never enter the real economy.[2] Since neither the banks nor anyone else can use them to buy goods and services, how can creating bank reserves cause inflation?

To understand what is happening and answer these questions we need to understand the money system.

[1] This paper leans heavily on a number of sources on Modern Monetary Theory. These include Stephanie Kelton’s The Deficit Myth, and many episodes of The MMT Podcast with Christian Reilly and Patricia Pino, especially those involving the incomparable Steven Hail. It should be stressed that the following discussion only applies to countries that have monetary sovereignty, i.e., (roughly) issue their own currency and do not have to borrow material sums in foreign currencies. This includes countries such as the UK, US, Australia, Canada, Japan and New Zealand.

[2] See for example Jeff Snider’s ‘Bank Reserves Part 1: The Great Tease’. https://alhambrapartners.com/2018/05/08/bank-reserves-part-1-the-great-tease/

The best place to start the explanation is with commercial bank lending, where we come to the first incorrect picture many of us have in our heads. In the picture, banks open their doors and wait for depositors. Then, when they have deposits, they lend them out to borrowers. Banks are just intermediaries. No?

This is wrong. Banks do not need deposits to make loans: rather, commercial banks create deposits when they make loans.

When someone takes out a loan from a bank two things happen. Firstly, the bank makes a record in a spreadsheet of the amount the borrower owes, and the terms of the loan (interest rate, timing of payments, and so on). Secondly, the bank creates a new deposit: it increases the balance in the borrower’s account by an amount equal to that of the loan and makes a record of this number in another part of the same spreadsheet.

A loan is an asset of the bank, because it generates cash flows for the bank: the borrower has to make payments of interest and repayments of principal. Conversely, a deposit is a liability of the bank owed to the depositor: it represents rights the depositor has against the bank. For one thing, if you have a deposit of $100, the bank has to give you $100 in bank notes when you ask for them.

You can exploit this claim on the bank in other ways. Let’s say you want to pay $100 to someone who has an account at the same bank. Easy: you tell the bank to debit your account and credit the recipient’s. From the bank’s perspective nothing material has changed – it still has a liability to produce $100 of bank notes. Only the beneficiary has changed.

But what if you want to pay someone who has an account at another bank? This is more complex.

Call the payer Alice and the recipient Bob. Alice’s bank is Bank A, Bob’s is Bank B.

Alice tells Bank A to send Bob $100. But Bank A can’t simply adjust Bob’s balance like it can Alice’s, because Bob’s account can only be adjusted by Bank B. So how does it get Bank B to make the necessary change to Bob’s account?

Bank B won’t just add $100 to Bob’s account because that is – remember – a liability to pay $100 in bank notes, of which Bank B has a limited supply. Bank B needs to be given an offsetting claim on someone else to pay notes to Bank B if and when Bob asks for them.

One way to do this is for Bank A to open an account for Bank B. Then it can debit Alice’s account and credit Bank B’s account. Now Bank B has a deposit at Bank A and so a source of bank notes it can call on to pay Bob if he demands notes.

But a problem arises if Bank B doesn’t trust Bank A to deliver the notes when asked. After all, in history lots of banks have proven uncreditworthy. What Bank B wants is a 100% reliable source of bank notes. Step forward the central bank: the only body that can print bank notes.

Each of Bank A and Bank B has an account at the central bank. The central bank credits a deposit to each account. These special deposits which banks hold at the central bank are called bank reserves. Like deposits at commercial banks they represent a right to ask for bank notes.

The difference is that the central bank, unlike commercial banks like Bank A and Bank B, can print bank notes in whatever amount it wants. Since reserves represent a claim to deliver bank notes on demand, and the central bank can print as many notes as it likes, it can also create as many reserves as it likes.

So instead of opening an account for Bank B and creating a deposit, Bank A can transfer $100 of reserves from its account at the central bank to Bank B’s account. Now Bank B has a claim on the central bank for $100 in bank notes. And this claim is 100% safe, because the central bank can print bank notes and so can never fail to deliver.

Note that the reserves created by the central bank never leave the central bank: they only move between the accounts of the different banks. Here we find another misleading picture: – talk of ‘reserves’ suggests banks have money ‘in reserve’ which they can ‘lend out’ to their customers. But they don’t.

In sum: bank reserves are a means of settling payments between banks.

In practice, Bank A and Bank B will be asked to make many payments to each other over any given period. Let’s assume these payments must settle once a day. At the end of each day, the amount of reserves Bank A needs to pay to Bank B is simply set off against the amount Bank B needs to pay Bank A, and each bank adjusts the balances in its own depositors’ accounts. Remember that a bank doesn’t care to whom it has liabilities, only the total amount of the liabilities compared with the size of its claim on the central bank to deliver bank notes. If the amount of reserves Bank A owes Bank B in respect of a given settlement period are the same as the amount owed to Bank A by Bank B, no transfer of reserves is needed. But if one bank needs to pay more reserves to the other than it stands to receive it will make a transfer equal to the difference.

This netting of payments means that in practice banks in fact do not need to have the same amount of reserves as they have deposits. Only to the extent that payments from one bank to another do not match the payments in the opposite direction is there a need to transfer reserves from one bank to the other.

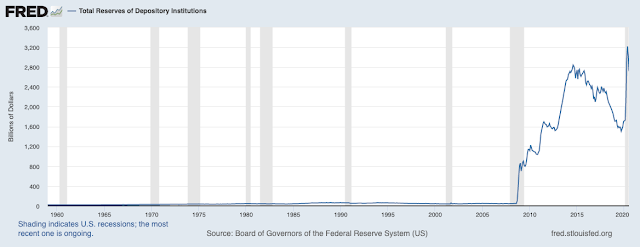

Since the system only needs enough reserves to settle this net amount, the amount of reserves that is required in the system is very small compared with the total amount of transfers, and also very small compared with the total amount of deposits held at the banks. For this reason, the total amount of reserves in the system historically has been very small compared to the size of the balance sheets of the banks. (This has changed with QE: see below.)

Sometimes a bank may find it does not have enough reserves at the central bank to settle the net transactions for a given period. In this case it can ask other banks to lend it some of their surplus reserves. Banks pay interest on such loans. This creates a cost for banks and indirectly influences the rates they charge their customers.

Consequently, it represents a tool the central bank can use to influence bank lending: indeed, most central banks have historically regarded this rate as the key monetary policy tool. In normal times, at any moment the central bank has a target rate that it wants banks to pay on these loans, according to whether it wants the banks to do more or less lending. (In the US this is called the ‘federal funds rate’.) It attempts to hit that target rate by adjusting the amount of reserves available in the system.

Note that for such a policy to be effective the central bank must keep the volume of reserves in the system low: if all banks have ample reserves they will not need to borrow from each other and the rate on interbank lending of reserves will fall to zero.

The central bank can reduce the amount of reserves in the system by having the government issue bonds to the banks and taking payment in reserves. In effect, it swaps bank reserves for government bonds. Historically, reserves did not pay interest, while government bonds did, giving the banks an incentive to swap one for the other.

QE has changed the functioning of this system. A central bank engages in QE by buying large volumes of financial assets (usually, but not always, government bonds) from private investors. But it is very important to note that, since a central bank can only pay for these assets using bank reserves, and only banks can have accounts with the central bank that can be credited with new reserves, central banks can only buy assets directly from banks.

When a central bank buys assets from a bank all that happens is a change in the levels of reserves in the system. However, the central bank can also buy assets from a non-bank by using a bank as a sort of intermediary. In this case both bank reserves and new deposits – real money in the real economy – are created. This is best explained by an example.

Let’s say the Bank of England wants to buy £10m of gilts from a financial institution that is not a bank – Aviva, for example. And let’s assume Aviva has an account with Barclays Bank. In order to pay for the gilts the BoE wants a new deposit of £10m to arrive in Aviva’s account at Barclays. The BoE cannot make this adjustment: only Barclays can. So the central bank directs Barclays to credit Aviva’s account with £10m. Since this creates a £10m liability on Barclays – namely, a liability to deliver either bank notes or (more likely) bank reserves to settle payments to be made in future by Aviva – Barclays will require the central bank to add £10m in reserves to Barclays’ account at the central bank before it credits Aviva’s account at Barclays.

In other words, in effect, Barclays buys the gilts from Aviva by exchanging them for a (newly created) deposit in Aviva’s account at Barclays, and then the central bank buys the gilts from Barclays by exchanging them for bank reserves.

Two asides at this point.

Firstly, we said above that traditionally the volume of reserves in the system was kept very low. The process of QE, as described in the previous paragraph, has transformed the picture entirely. The chart below shows the total level of reserves in the US banking system since 1959. Note that the level of reserves was almost zero until QE was launched in 2008.

Now consider where the money has landed after this example of QE: in the bank account of Aviva, or strictly speaking, one of Aviva’s investment funds. What will this money be used for? The precise answer is that it depends on the rules the fund must abide by. But, since this is a fund whose job is to invest money, these rules will almost certainly limit the use of the money to investment in other financial assets. Even when the central bank buys financial assets from the public, the sellers are likely to be wealthy individuals or families who themselves will reinvest the proceeds rather than spend them.

The result we would expect from this type of quantitative easing is therefore an increased supply of money chasing financial assets. And note that through QE the central bank is reducing the supply of financial assets by buying them.

Let's take the US as an example once again. In 2020 the US has issued a huge volume of Treasuries, but it has bought a lot too into its System Open Market Account (SOMA), and more still have matured and fallen out of the market. The table below shows the total figures for 2020 to the time of writing.

So on a net basis $730bn-worth of US government bonds have been taken out of the system this year. More money chasing fewer assets can have only one result: a rise in asset prices.

But we would not expect to see a material effect on spending, i.e., on activity in the real economy. And this, it would appear, is the explanation for a conundrum: how can it be that financial markets are booming while the economy is struggling so badly? The answer is that QE does increase the money supply in a meaningful way, but that this leads primarily to asset price inflation and does very little to encourage demand and therefore spending, which is what the real economy needs.

There is much more to say about the background of this system. And this only begins to hint at the implications of its functioning. But that’s probably enough for one post.

Excellent post - thank you

ReplyDeleteThanks! Do let me know if you have any questions.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteHI Matthew

ReplyDeleteThanks for this. Its helped clarify a murky area for me. But it’s also raised some additional questions which I’d be grateful if you could help me with.

You say “Banks do not need deposits to make loans:”. This raises two questions (which may answer themselves)

1. Where does the loan money come if not from depositors. Is it the banks own capital?

2. Why do banks bother with deposits if they don’t need them to make loans.

B. I can see how the central bank can act as a clearing house for interbank liability settlement. Is that the only purpose of the Central bank reserve account or are there other purposes. If so what determines how much a bank keeps in its reserve account

C. You say the Fed “can print as many notes as it likes (so) it can create as many reserves as it likes.”

Why would the Fed “print” reserves rather than have the commercial banks create them by depositing funds with the Fed.

d. What is the mechanism by which a bank requests a loan of CB reserves from other banks. Is this the Repo window?

e. How does the Fed adjust the amount of reserves in the system to influence the Fed Funds Rate.

f. You say “The central bank can reduce the amount of reserves in the system by having the government issue bonds to the banks…”

How does the Fed induce the government to issue bonds to the banks.

Thanks

Kevin

Hi Kevin

DeleteThese are all good questions. Let me see if I can answer them in a helpful way. I haven't followed your numbering (partly because it is a bit confusing) but I have tried to follow the order of your questions.

1. When a bank makes a loan it does not get money from anywhere. Rather, when a bank makes a loan an officer of the bank simply makes two entries in a spreadsheet: one records the terms of the newly created loan, and one records the amount of the deposit. The first is an asset of the bank and the second is a liability.

2. Banks make profits on their lending business, and lending requires the lending bank to create deposits in the way described. They don't 'need deposits' in the sense that they first take a deposit and then lend it out, but loans and deposits must be created at the same time.

3. There is more than one use of central bank reserves. Two more are actually described in the text. Firstly, reserves are used by banks to acquire government bonds. Secondly, the central bank creates new reserves to buy financial assets directly from banks (and indirectly from non-banks) when it carries out QE. In addition, the mechanism by which the central bank buys financial assets from banks using reserves is exactly the same mechanism that the state uses whenever it buys anything from anyone. This is a big and very important topic which I will write about separately.

4. It is the central bank which decides on the volume of reserves in the system. As described in the text, they traditionally keep the level of reserves very low so that the rate of interest on loans of reserves is positive (if there are too many reserves no one would need to borrow them and the rate would fall to zero). If a bank finds itself running short it can either try to borrow from another bank (as described in the text) or go to the central bank to ask for more. This latter tactic is usually frowned upon by central banks as it means creating additional reserves and therefore reducing the central bank's control over interest rates on overnight loans of reserves. Of course in the era of QE the banks are drowning in reserves and this is not an issue.

5. While my explanation of the money system began with commercial bank loans and deposits (I find this the best way to explain it), the story really begins with the central bank, which in the modern system is the ultimate source of all money. Remember that a commercial bank deposit is (inter alia) a promise to deliver a certain volume of bank notes on demand. The commercial bank can only get bank notes from the central bank, as this is the only legal source of such notes.

6. Every bank's treasury department has a desk for borrowing and lending reserves. When a bank needs to borrow or wishes to lend surplus reserves the desk just calls the desks at other banks.

7. The Fed / central bank adds reserves to the system by amending the balances in the reserve accounts of the banks at the Fed. Sometimes this involves buying assets (usually government bonds) from the banks. The Fed drains reserves by selling government bonds to the banks - either newly-created bonds or bonds it previously purchased and held in inventory.

8. The central bank is just an arm of the state (there is a lot of confusion about this because strictly speaking some central banks have private shareholders, but this doesn't make any difference in practice). So it isn't really a case of the central bank 'inducing' the government to issue bonds: it's really the central bank which decides when to issue, buy or sell government bonds in order to carry out its monetary policy.

As I mention above I am going to add a couple more posts on this topic expanding on the original post. Hopefully the answers above plus the posts to come will help you get your head around all this.

I hope this is helpful

Hi Matthew,

DeleteThanks so much for this. Apologies for the confusion in numbering. I had a number of questions jumping around my head and I think I tripped over myself.

As context for my questions, I am trying to understand these issues through the lens of transactional flows. Where money comes from ; how it moves and what’s its effect on the source and receiver after it moves. In this regard let me clarify my question. (Numbers refer to your answers)

1.& 2. While I understand that in practice a bank issuing a loan is just a ledger transaction. They do have limits on their ability to issue which I understand are based on the reserves ratio. What is the source of funds for these reserves? I had thought it was savers deposits, If not those then where does it come from.

a. To give a concrete example. I’ve just opened the Bank of ME (BOM) and you’re my first customer. How much can I loan you and where am I getting my money from?

3. As the BOM I can use my reserve account

a. As a means to settle liabilities with other banks

b. As a way to earn money by loaning reserves to other banks . Question: Does the Fed backstop these loans or is it my risk?

c. To buy Government bonds . Question: does that reduce my reserve balance or do the bonds count toward my reserve holding requirements.

4. Few questions here:

a. Other than the Reserve Ratio how does the central bank control the volume of reserves.

b. When you say they like to keep them low. Low is relative to what?

c. For a QE transaction the bank has first to buy the bond it’s going to sell to the CB. Which means it needs to use its own capital (or reserves). What’s the incentive for the bank to sell that income producing asset to the CB when the proceeds can only be used for reserves

Following on from above. In the example of QE you gave in your original post you said there was a difference in impact between the CB buying bonds directly from banks and indirectly from non-banks. I don’t understand why it’s different. The CB is always just dealing with banks. The banks are dealing with a different source for the bonds however in your example Barclays is using its reserves (or capital) to buy the bond from Aviva – just as it would if it were buying it directly from the Treasury so it doesn’t seem to be creating “new” money.

Additionally Aviva had money to buy the bond to begin with and now that they have sold it though don’t seem to have any more money than they had before, or am I missing something.

Finally you say that this extra money chasing a smaller pool of assets (due to QE) results in asset price inflation, but does it? Bond issuance by governments has skyrocketed since QE started . the investment pool has if anything got bigger.

Thanks for taking the time with this. I feel we might be talking past one another – which is probably due to large blanks in my understanding of these topics. Appreciate your help.

No problem with the numbering, and no problem with the questions. I have worked in finance for well over twenty years, and I didn’t understand all this until relatively recently either. It has taken me a lot of time and effort to figure it out.

Delete1. Reserve requirements are meaningless, because if a bank needs reserves it can always ask the central bank for more (though not without getting a stern lecture). This is shown by the fact that many countries including the UK have no reserve requirements, and though the US strictly speaking does have a reserve requirement it is currently set to zero.

2. What limits the amount a bank can lend is not its reserves but its capital. This is a complex story (I would need a post at least as long as the original). The basic idea is that capital (roughly, the equity and subordinated debt of the bank) protects depositors and other creditors because the owners of the capital (i.e., the shareholders and subordinated lenders) bear the first losses made by the bank. The idea is that the bank should only be allowed to take an amount of risk which ensures its capital adequately protects its senior creditors (i.e., the bank won’t suffer losses greater than its capital).

3. I’m not sure of the precise arrangements for loans of reserves between banks, and in particular not whether the Fed explicitly ‘backstops’ those loans, but ultimately the central bank can and will always step in to create reserves as they are required to ensure the smooth functioning of the system.

4. Buying government bonds from the central bank always reduces a bank’s reserves. Government bonds are not reserves.

5. The central bank controls the volume of reserves by buying and selling government bonds. The state (of which the central bank is a part) can also increase the amount of reserves by spending and reduce the amount of reserves by levying taxes. This latter process is explained in the second post – not sure if you have read that one yet?

6. Central banks historically kept reserves low relative to the total amount of deposits held and transactions carried out by banks. Remember that reserves function primarily as a settlement mechanism for payments between banks but also that every payment in the system is someone else’s receipt. This means that across the system as a whole all payments and receipts net to zero. There can however be small mismatches between the payments and receipts of an individual bank: these mismatches are balanced out by the transfer of reserves between that bank and others with whom it has net payments or receipts to settle. NB I have added a chart to the main article which shows the level of reserve balances in the US system since 1959, together with some explanatory commentary. Essentially balances were almost zero until QE was first carried out in 2008.

7. Central banks buy assets from all sorts of market participants. When they buy from a bank directly, they do say by creating new reserves and there is no further consequence outside the banking system. But when they buy from a non-bank, things are different. Here, firstly the non-bank sells to a commercial bank in return for a new deposit, and secondly the commercial bank then sells to the central bank in return for reserves. So when the central bank buys assets from non-banks both reserves and deposits are created.

8. The incentive for a bank to sell a bond to the central bank is simple: price. When the central bank engages in QE, it has to pay a high enough price to acquire all the bonds it wants, which will be above the market price. What is more, in the era of QE central banks now pay interest on reserves – not very much, but then rates on government bonds are very low too.

9. Finally, it is true that the US has issued a lot of government debt in 2020, but the net effect of issuance, QE purchases and bonds maturing means that the volume of US government debt in the system has fallen by $730bn in 2020. I’ve added some figures from Bloomberg and commentary on this to the piece as well.

Hi Matthew,

ReplyDeleteFound u here from link u showed at RV. This is a ton to digest, and then to try to compare and contrast with previous descriptions I've read or heard thru podcasts. I'm not in the industry. Would u mind sharing some info on the origins of your description. Can u provide references to other docs? Perhaps tell us something about your background that would help us understand your perspective, and honestly, to help me justify the labor I'm going to have to undertake to read and re-read your description. Ha! Much appreciated.

Wade

Hi Wade

DeleteThanks for the comment and questions. Like you (!) I felt there was a lot to digest in this first post but it's hard to explain one part of the system without explaining others.

The best sources I have found on this subject are generally economists of the MMT school. I don't necessary accept everything they say, but their grasp of the money system is usually pretty solid. I would recommend these in particular:

1. A good place to start is Randall Wray's essay in 'Modern Monetary Theory and its Critics' (link below). The essay is called 'Alternative paths to modern monetary theory'.

https://www.amazon.co.uk/gp/product/B085632KFL/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_search_asin_title?ie=UTF8&psc=1

2. I would also recommend this interview with Steven Hail by The MMT Podcast. It's dry but very complete, clear and accurate:

https://pileusmmt.libsyn.com/13-steven-hail-everything-you-always-wanted-to-know-about-banking-but-were-afraid-to-ask

As for me, I have been in structured finance since 1997, working at a series of investment banks (BarCap, UBS, Commerzbank, HSBC). You don't need to understand the monetary system in this level of detail to be a banker (or vice versa): I started taking an interest in this subject over the last few months as I wanted to get to the bottom of what was happening in the structured bond and ABS markets and found myself digging deeper and deeper.

While this discussion is based on the sources above (and others), I have never seen anyone put it all together in quite the same way as I do. In particular I don't think commentators correctly characterise the relationship between deposits, reserves and bank notes. I think a lot of people think bank notes are sort of a relic and an optional extra, but they seem to me to be very important, for reasons I will explain in a future post - and which I hope will cast light back on this first one.

I hope this is helpful. Do let me know if you have more questions.

I'm going to add some more posts over time to try and provide a complete picture, but (like you!) I felt like there was a lot to digest in the first post

Matthew, this was helpful, thank you for the additional info. Work to do.

DeleteVery interesting! Thank you for your efforts in writing this out!

DeleteI still have a question bothering me with respect to QE introducing liquidity. Everything you have laid out mostly makes sense to me, including "In this case both bank reserves and new deposits – real money in the real economy – are created."

However, when the CB (indirectly) purchases a bond from a primary dealer, it also removes that bond from the real economy. Can't we also consider that that bond was already somewhat-less-liquid money? After all, the PD could easily have liquidated it on the market. Isn't it then unfair to say that money was truly created by QE (although M2 definitely increased)? Isn't this just an accounting trick?

I do agree that QE can and seems to inflate financial markets by encouraging a reshuffling of these sums. Would it be correct to say that if the PD simply repurchased the same type of bond with the money from QE, we would be back to square one, albeit with lower treasury yields (due to reduced supply and unquenchable fed demand in the bond market)?

Thanks again!

Very interesting! Thank you for your efforts in writing this out!

ReplyDeleteI still have a question bothering me with respect to QE introducing liquidity. Everything you have laid out mostly makes sense to me, including "In this case both bank reserves and new deposits – real money in the real economy – are created."

However, when the CB (indirectly) purchases a bond from a primary dealer, it also removes that bond from the real economy. Can't we also consider that that bond was already somewhat-less-liquid money? After all, the PD could easily have liquidated it on the market. Isn't it then unfair to say that money was truly created by QE (although M2 definitely increased)? Isn't this just an accounting trick?

I do agree that QE can and seems to inflate financial markets by encouraging a reshuffling of these sums. Would it be correct to say that if the PD simply repurchased the same type of bond with the money from QE, we would be back to square one, albeit with lower treasury yields (due to reduced supply and unquenchable fed demand in the bond market)?

Thanks again!

Hi there

DeleteThanks for the comment and for your kind words.

It isn’t really right to say that when a central bank buys a bond it removes it ‘from the real economy’. It buys it from a financial markets investor, not a participant in the real economy. One of the key points I was trying to make is that the state needs to stop buying financial assets from financial markets investors and start spending money in the real economy. There is a shortage of private spending in the real economy – there has been such a shortage for a long time, but during the lockdown matters deteriorated significantly – and if calamity is to be avoided public spending has to replace it. Otherwise businesses will continue to fail and jobs will continue to be lost on a vast scale.

You are right though to say that we can consider government bonds as a kind of money: just like bank reserves they are a promise to pay which can ultimately be settled with bank notes. I have heard several commentators point out that we could simply replace government bonds – long-dated, interest bearing obligations of the state – with term savings accounts at the central bank, which would be functionally pretty much identical with government bonds. These savings accounts would sit alongside the ‘current accounts’ at the central bank in which banks keep their reserves. Many definitions of money include term deposits such as these.

This is a serious suggestion by the way, though of course it is a heretical one among my former colleagues in the investment banking community. Since reserves now pay interest, and have been created in immense amounts, government bonds are superfluous. Remember they were originally supposed to provide an interest-bearing alternative to (non-interest-bearing) reserves, so that issuance drains reserves from the system to allow central banks to manage interbank interest rates. With QE this is impossible – the volume of reserves created means no more borrowing of reserves, so interest rates are zero – and obviously unnecessary. What is more, if we got replaced government bonds with central bank savings accounts everyone might just stop having conniptions about the ‘national debt’.

Great post; thanks! In particular, this cleared up one question I had lingering re: the mechanics of how/why reserve assets created by QE typically find their way into asset prices.

ReplyDeleteHey Matthew,

ReplyDeleteGreat Post!

Could you please provide references for the below happening in the US?

"However, the central bank can also buy assets from a non-bank by using a bank as a sort of intermediary. In this case both bank reserves and new deposits – real money in the real economy – are created. This is best explained by an example."

Hi there

DeleteThe US system is even more confusing than the capers described in my blog, because the Fed actually faces 24 "Primary Dealers", none of whom are banks, and all their sales and purchases are settled by a single bank (BoNY). This introduces a whole additional layer of complexity. In the original posts I tried to be as generic as possible rather than getting into the weeds of the individual systems, because I thought the important thing was to establish the principles. However, I might add another post about the US system in particular because it is so important (and because I find it so interesting).

In the meantime, if you want to learn more about how the system in the US works you could take a look at Zoltan Pozsar's paper at the link below, which is about as complete an explanation as I have seen. Be warned though, it is extremely complex and I'm not sure he has every detail right.

https://plus.credit-suisse.com/rpc4/ravDocView?docid=V7hgfU2AN-VHSK

Another excellent paper which sets out some details of the US system is this one by Stephanie Kelton (writing then under her maiden name, Stephanie Bell). This is one of the foundational texts of MMT and well worth a read in any event.

http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/wp244.pdf