How the money system works, part 3 – summary and consequences

This has been a dry and technical discussion so far. But everyone should take the time to understand it, because the political and economic consequence are immense.

Before explaining why, let’s recap.

- When a bank creates a loan it creates both an asset (a claim for payment on the borrower) and a liability (the borrower’s deposit).

- This liability amounts to a promise to deliver bank notes up to the amount of the deposit, or alternatively to use its bank reserves to settle payments made by the deposit, also up to the amount of the deposit.

- Bank reserves are amounts held by commercial banks in accounts at the central bank. Like commercial bank deposits, they are a promise to provide bank notes on demand. The key difference is that the central bank can create bank notes (or reserves) at will, whereas a commercial bank cannot.

- When a depositor instructs a bank to move money to an account at another bank, the first bank transfers reserves to the second bank, and the second bank then creates a new deposit in the account of the recipient of the payment.

- In other words, reserves are a means of settling payments between banks.

- In practice banks settle payments between themselves on a net basis. As a result the amount of reserves required in the system is relatively small.

- Banks who do not have sufficient reserves to settle all their payments over a given period can borrow reserves from other banks. When they do so they pay interest on what they borrow.

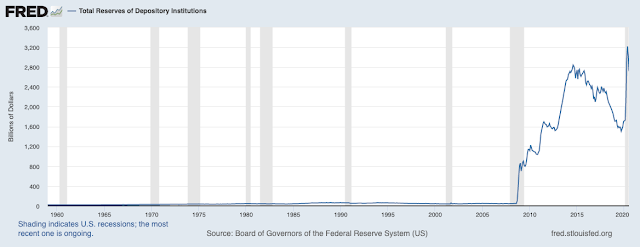

- In normal times, central banks regard this interest rate on reserve borrowings as a key monetary policy tool. In order to make sure this interest rate is greater than zero central banks tend to keep the volume of reserves in the system relatively small.

- To manage the volume of reserves in the system the state issues and repurchases government debt.

- Central banks carry out QE by buying large volumes of bonds from non-bank investors. They do so indirectly, in a two-stage process: first, the investors sell the bonds to banks in return for deposits, and secondly the banks sell the bonds to the central bank in return for reserves.

- The consequence of this is that, when central banks engage in QE, deposits are created in the bank accounts of investors, who generally reinvest it rather than spending it.

- Because the central bank has increased the money in the accounts of investors but shrunk the volume of financial assets available (by buying some of them), the prices of financial assets will tend to rise.

- However, since very little of this money finds its way into the pockets of participants in the real economy[1], it does nothing to help them. This is (at least in part) how it is possible for financial markets to boom while the economy struggles.

- The government does not fund itself by levying taxes. Instead, it levies taxes in order to prevent inflation by removing money from the system altogether.

- Most importantly, the state creates money (in the form of both bank reserves and bank deposits) when it spends. It does not need to get money from any third party in order to spend – whether through tax, through borrowing, or via any other means. As a result there are no financial constraints on state spending – as we see in time of war.

It is even more important to understand how radically this description of the functioning of the money system departs from the mainstream views based on the pictures we have rejected. The following points in particular are of great importance:

- Readers will see politicians, economists and other commentators suggest that it is acceptable for governments to run big deficits now because interest rates are low and debt service costs are minimal. But this is nonsense. The state can always service its debts because it can always create the money it uses to pay interest and principal.

- For the same reason, concerns that the national debt will be a burden on our children is also nonsense. The debt isn’t a burden at the moment and won’t be in future, because the state, in the form of the central bank, can just print money to pay it off or buy it back.

- Sometimes you will see the same commentator both worry that central bank ‘money printing’ will cause inflation and that we will never be able to repay all the debt governments are issuing. But if governments can print money, why do they borrow so much of it?

- In fact, the state does not need either to borrow or to levy taxes to ‘fund’ its spending. Rather, it creates money through the act of spending.

- The process is the same as in the case of QE, and involves the central bank creating reserves and commercial banks creating deposits.

- The state can create and spend as much money as it likes on whatever it wants. Consequently, if any public service is underfunded or under-resourced this is the result of a political decision, not a lack of money.

The significance of this last point can hardly be overstated. Every time a school lacks basic resources, when a road or bridge goes unrepaired, when people die of Covid because of a lack of protective equipment this is never because there isn’t enough money. Again: the state can create and spend as much as it likes on whatever it likes.

So now ask yourself these questions:

· Why aren’t these facts more widely known?

· Why do politicians and sometimes even economists and central bankers so often behave as if this were not the case? Do they not understand, or are they being mendacious?

· What could we do for families, workers and businesses if these insights were widely understood?

[1] Investors take a small amount of the income their funds earn to pay their costs, including fees to other businesses such as auditors, tax and other advisors and trustees. They also pay salaries to their employees. This money does find its way into the pockets of people who may spend it.

Matthew, thanks so much for this, and, at last, an analysis taken to its logical conclusion. It's not just mendacity though is it? The whole tax / spend / Budgetary Stance thing is a major feature of our pre and Undergrad Uni Macroeconomics courses. We are systematically teaching a deception to our young. And I'm a teacher! Maybe this is why there has been no serious effort to raise the level of basic financial education generally, in case we inevitably stumble upon this particular Wizard of Oz.

ReplyDeleteCheers mate. Keep it up.

Thanks. Keep fighting the good fight.

Delete