How the monetary system works, part 2 – taxation, inflation, bank notes and gold

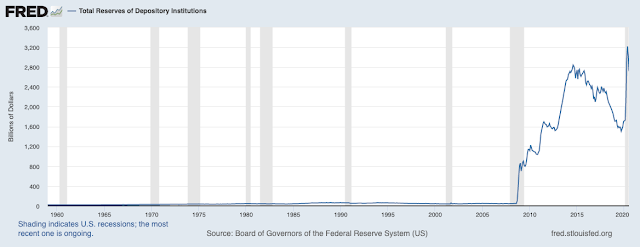

We saw in the last post that – contrary to the opinion of some commentators – QE does involve meaningful creation of money in the form of bank deposits. But we also saw that it puts that money in the hands of people who simply reinvest it in financial assets. What the economy needs, if it is to recover from the pandemic and grow, is not reinvestment but spending – real economic activity by actors in the real economy.

So what should policymakers do? How can spending in the real economy be encouraged? Well, the obvious answer is that money must be provided to participants in the real economy, not simply to investors. How can this be done?

This is where we come up against another false picture that influences our understanding of money and the economy, namely, the picture we have of taxation and government spending. In this picture, the government takes money from people and businesses in the form of tax and then spends it. Just as in the case of loans and deposits, experts and laymen alike are mesmerised by this picture, which seems to be so obviously correct as to be entirely beyond question.

But it is wrong. Indeed, it is exactly backwards.

In the previous post we described the process by which the state, in the shape of the central bank, purchases financial assets from non-bank investors. It is of the first importance to note that the central bank does not need to get money from anywhere to do this: it simply increases the amount of reserves in the account of the investor’s bank, and the investor’s bank then creates a deposit of the same amount in the investor’s account.

Now we arrive at another important point. This is what the state does when it spends money on anything, not just financial assets. So, imagine that instead of buying £10m-worth of gilts from Aviva, the state wanted to buy £10m-worth of military equipment from BAe Systems, who also bank with Barclays. In exactly the same way as we described in the previous post, the Bank of England (at the instruction of the Treasury) increases the reserves in Barclays’ account at the central bank, and Barclays credits BAe Systems’ account at Barclays with a £10m deposit in return for delivery of the equipment. The money the state spends does not come from taxation: it does not ‘come from’ anywhere. The same goes when the state makes welfare payments: if it wants to pay £1bn in pensions or unemployment benefits, or recruit and pay a few thousand nurses or teachers, or pay everyone in the country a monthly sum by way of ‘universal basic income’, or whatever – it instructs the central bank to create that amount in reserves, and the central bank instructs the commercial banks to create new deposits in the same amount in the accounts of their customers who are the claimants.

But wait, you may be thinking. If all this is true, and the government does not need to levy taxes to pay for its spending, why does it levy taxes at all? And at the same time you are probably becoming uneasy about inflation. If the government just created money at will and spent it, or gave it to people, wouldn’t that cause runaway inflation? Won’t we end up like Zimbabwe, or Weimar Germany?

Before we answer this question, let us first understand how the state levies taxes. When a taxpayer comes to settle up with HMRC, she instructs her bank to make a payment to HMRC – just as she would make a payment to anyone. Her bank debits her account in the amount of her tax bill, but instead of transferring bank reserves to another bank as it would in the case of any other payment, the taxpayer’s bank transfers bank reserves to the account of HMRC, which is held with the central bank. Also unlike the case of other payments, no new deposit is created at a commercial bank to replace the taxpayer’s original deposit. In other words, the total supply of deposits in the commercial banking sector has fallen.

Taxation therefore works in the opposite way to government spending. When the state spends, it creates bank reserves and commercial banks create new deposits which can be used in the real economy. And when the state levies tax the process is reversed: deposits and reserves are extinguished. Taxation is not a source of funding for the government: it is a way of managing the amount of money in the real economy.

People like to regurgitate Milton Friedman’s famous quote to the effect that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.”[1] They rarely cite the rest of his words, where he carefully says that he means that inflation “is and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.” [emphasis added]

In other words, it is not true that ‘printing money’ always causes inflation. What is true is that there will be inflation if the money supply increases and there is no corresponding increase in the supply of goods and services that the money can be spent on.

The complex story of hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic[2] begins with a fall in the value of the German currency, which drove the price of imports higher. The central bank started printing more notes to keep up with price rises, and increased the wages of state workers to keep pace. Then the German state defaulted on its payment of reparations for world war one, and the French and the Belgian armies invaded the Ruhr – the home of Germany’s mining and manufacturing industries. The workers in the Ruhr downed tools and production ceased. But employers kept paying salaries, and the government kept printing money to pay reparations and wages. As the supply of goods and services fell to near zero and the amount of money available accelerated, hyperinflation was inevitable.

Zimbabwe was similar. Food production collapsed when farms were taken from white farmers who produced most of the food supply and handed to inexperienced black Zimbabweans. Failure to invest in infrastructure meant that primary industries could not transport raw materials either for export or for use by domestic manufacturers. Foreign currency reserves were used to import food, meaning manufacturers could not get materials from abroad either. Importers faced with high tariffs stopped bringing foreign goods into the country. And the government kept spending, partly to finance its extraordinary corruption. An increased money supply against the background of almost zero availability of goods and services again resulted in hyperinflation.

But now imagine that the government gave a million people in the US a voucher worth $10,000 towards the cost of a new car. Would this cause inflation – that is, would it cause the price of cars to rise? The answer is almost certainly not, because the auto industry has a significant amount of spare capacity.[3] To build the new cars to meet the demand created by printing the vouchers the industry would just need to pay a few workers to work more hours and fire up its currently mothballed factories. Only if there is still increased demand when all the spare capacity is used up – that is, when supply can no longer easily rise to meet that increased demand – will prices start to rise.

It is instructive to consider the case of wartime.[4] Many people have remarked on the way in which (at least in the modern world, under the modern monetary system) governments always seem to have plenty of money to fight wars, even as they claim they cannot afford to pay for other things, such as health and education services. The discussion above should make clear that the issuer of a currency always has limitless money to spend on whatever it wants. For some reason, they seem to be rather shy about spending most of the time. But when a war comes along, they shed all inhibitions.

When the United States entered world war two it did not do things by halves – as you would expect from any country that regards itself, its people or its allies as being in imminent danger. Maximum resources were enlisted to fight the war. Anyone who wanted work could find it. Huge sums of money were created to pay for military equipment and to hire and provision immense armed forces. Vast parts of the economy shifted from producing goods for domestic consumption to producing the means of waging war.

The inflationary potential of this is obvious. Imagine pumping large sums of new money into an economy just at the moment that you are restricting the supply of goods that the recipients of that money – the factory workers with their higher wages, the company bosses with their bigger bonuses, the investors with their bigger dividends – can spend it on.

But the United States did not suffer a runaway rise in prices during world war two. The reason is that, while they were spending, they also raised taxes and issued huge amounts of debt to drain reserves and deposits from the system. And they directly asked the public to exercise restraint in spending. Contemporary advertisements show wage packets filled with dynamite and warned of the hazards of spending too much. The state issued ‘war bonds’ to be redeemed only after the fighting stopped, thereby deferring consumption until after the war. It was made clear that paying higher taxes, buying war bonds and exercising restraint in spending were everyone’s patriotic duty. These were all ways of controlling inflation. All worked. And none of them had anything to do with ‘paying for the war’.

We started by asking how policymakers should encourage spending in the real economy. The first part of any answer is – the state itself needs to start spending, in large amounts and quickly. At a time when millions are out of work and businesses are collapsing there is a shortage of private sector spending (as indeed there has been for a long time, explaining the failure of central banks to meet their inflation targets for many years – though just now it is extreme). The answer is to increase public spending – which is essentially what Keynes said, years and years ago.

The discussion above shows that increasing public spending is easy and costs nothing: the central bank creates more reserves so that the commercial banks can create more deposits. This puts money into the real economy, which many fear is inflationary – but the risk of creating meaningful inflation is almost nil because of the immense spare capacity in an economy where millions are unemployed and businesses are going bust precisely because spending has collapsed.

Of course, there has been some consumer price inflation during the lockdown, because governments gave people money while production ceased almost completely. Look at the graph below, which shows the movement in the Manheim Used Vehicle Index, a way of tracking second-hand car prices in the US. Used car values exploded during lockdown. Why? Because there was some level of demand for cars and no one was making new ones.

We need public spending on a large scale, and fast. This is something to be welcomed, not feared. The alternative is a depression. Avoiding depression is easy, costs nothing and will not trigger inflation. All it takes is a little effort to understand the monetary system.

------------------------------------------------------------

There are many sources of the confusions surrounding the money system, but a very important one is the historical role of precious metals. A bank deposit is a promise to pay either notes or bank reserves; bank reserves are a promise to pay notes; and notes used to be a promise to pay a fixed amount of precious metal. This is why the discussion in the posts to date has drawn attention to bank notes, which are usually left out of discussions of the monetary system.

If you look at a UK bank note you will see that it still says the Bank of England “promise[s] to pay the bearer on demand the sum of five pounds.” The pound sterling is so called because at one time a pound coin was made of a troy pound of sterling silver. The bearer of a five-pound note had the right to demand five coins of that type, that is, five pounds of silver. At other times gold has, of course, played a similar role in the UK and many other countries.

Of course, it is no longer true that the Bank of England (or indeed any central bank) dishes out precious metals to note holders ‘on demand’. But that doesn’t make the promise on the notes meaningless. The Bank is still promising that if you turn up with a five pound note it will give you five one-pound coins on demand. Or, that if you present a twenty it will give you four five-pound notes, or whatever correct change you want for what you present.

This may sound trivial: an empty, meaningless promise to exchange pieces of worthless base metal or paper for each other. It is anything but. Once any link to precious metals is abolished, without central bank intervention of this kind there is no reason why a ten-pound note should be worth exactly ten times as much as a pound coin and twice as much as a five-pound note. There is no law of nature that forces everyone in society to value these things the same way. After all, they are just pieces of paper and lumps of base metal. But if there is someone who promises always to maintain fixed exchange rates between these different denominations, and who can always create the money sufficient to fulfil its promise, then those exchange rates are fixed for ever and for everyone. As Gareth Rule puts it,[5] “all transactions that settle using banknotes are done so because agents trust the value of banknotes. That is, they trust the central bank to maintain and honour the value of banknotes.”

When the world was on a gold standard, states had to be careful how much money they borrowed, because ultimately the lenders could demand payment in gold which the state could not manufacture. At that time it was possible for states to run out of money – that is, run out of gold – and bankrupt themselves. The central insight of the discussion thus far is that this is no longer possible for states that issue their own currency to default on payments in that currency, because they control the creation of money denominated in that currency. They create it when they spend it. They do not need to get money from anyone or anywhere else in order to spend.

We have come a long way. In our next post we will summarize the story so far. But there is much more to say.

[1] Friedman, Milton. 1970. Counter-Revolution in Monetary Theory. Wincott Memorial Lecture, Institute of Economic Affairs, Occasional paper 33, p.24.

[2] Explained very well by Bill Mitchell at http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=3773

[3] Recent estimates suggest that the US auto industry has ca. 20% overcapacity.

[4] This discussion is indebted to Sam Hervey’s excellent paper ‘Modern Money and the War Treasury’. http://www.global-isp.org/wp-content/uploads/WP-123.pdf

[5] Gareth Rule, ‘Understanding the central bank balance sheet,’ p.5. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/ccbs/resources/understanding-the-central-bank-balance-sheet.pdf?la=en&hash=0475942A8BE465179CF4CFB4996AF44CDACB1662

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteIf my reading of history is correct, I believe the troy pound was used as a standard during the 1500s, following a major debasement of the currency which contained only 33% silver and reduced their weight. So at this point, in 1552, 1 troy pound of sterling silver produced 60 shillings of coins (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pound_sterling#Tudor, which includes citations for the facts referenced). This appears to have more or less prevailed with slight modification until 1816, when 1 troy lb of standard (0.925 fine) silver was minted into 66 shillings. Given that 20 shillings is one pound sterling, we have a ratio of 3.3 pounds sterling per troy lb of 0.925 fine silver.

ReplyDeleteSorry if this is a bit rambling, but 1 troy lb is equal to 13.16571oz as measured today. Basic math would indicate to me that individuals who chose a precious metal as a store of value would have fared significantly better than holders of paper currencies over time.

Further, I'm not sold on the argument that banknotes are used to settle transactions because agents trust their value. They are used because their acceptance is legally mandated, because it is convenient to do so (generally easy for a layperson to determine authenticity, ease to transport, etc.), and because governments confiscated the gold of their citizens at various points in time to establish a fiat system.

Hi Ian

DeleteThanks for the comment. To be clear, I didn't mean to say anything about why bank notes are used to settle transactions, i.e., have value in the first place (though in retrospect maybe the quote I gave, taken from a BoE paper, might have been confusing, for which apologies). I only said that it is the central bank which guarantees the exchange rate between bank notes. In the absence of convertibility into previous metals (or whatever) you need something or someone to ensure a ten pound note is worth the same as ten pound coins or two five pound notes. But this doesn't explain why notes have value in the first place.

In actual fact I don't agree with your assessment of why bank notes have value, but that is a big and important story which I might save for a future post.